First Steps in Opensource Robotics and Imitation Learning

Intro

There’s a lot happening in robotics right now. I’ve been reading exciting papers about Imitation Learning like Action Chunking with Transformers (ACT) and Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model like Physical Intelligence’s \(\pi\) model family (e.g., \(\pi_0, \pi_{0.5}, \pi^{*}_{0.6}\)) and Hugging Face’s smolVLA. I’ve also been studying Robot Learning: A Tutorial by Francesco Capuano and colleagues, and frameworks like LeRobot.

I am super excited by these developments, and I have been keen to get hands dirty. I found Gavin Cangan at the ETH Student Project House, who was kind enough to lend me his SO-100 arm. Over Christmas, I played around with different hardware setups and models.

In this post, I’m sharing my experience and insights: setting up the robot, collecting my first dataset and training a imitation learning policies, extending my setup with a wrist camera, and why finetuning Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models didn’t bring the results I hoped for.

Grab a coffee and read along!

Chapter 1: Setup and Teleoperation

Setting everything up and doing my first teleoperation was surprisingly easy.

The SO-100 arm is an opensource robot arm from TheRobotStudio, which is very popular in the opensource community. This popularity stems from the easy availability of parts (you can even 3D print the robot) and the rich software resources available on the Hugging Face LeRobot platform. TheRobotStudio has released an improved version, the SO-101, but I worked with the SO-100 because I had access to an existing arm.

Hugging Face has a detailed setup guide that’s quite thorough and self-explanatory, so I won’t rehash it here. The setup worked very well for me: I got teleoperation working in about an hour. I had to reset the motor IDs and baud rates and calibrate the motors. The software setup was also super easy with a simple git clone and pip install (installation guide). I had teleoperation running in no time.

Technical anecdote: One interesting detail is that USB adapter placement matters. Since my laptop and the robot both have USB-C ports but the cables that came with the robot were USB-C to USB-A, I needed a USB-A to USB-C adapter. Initially, I attached the adapters to the arm, but in this configuration, the arm didn’t show up in /dev/ (lerobot-find-port couldn’t find a port). I had to connect the adapter directly to the laptop to make it work.

With the first setup ready, I could practice teleoperating the robot. I practiced picking up a flashlights and pens and placing them into a cup.

Chapter 2: Pick & Place with ACT

It was time to get real and collect some data, train a imitation learning policy, and make the robot work autonomously.

Data Collection

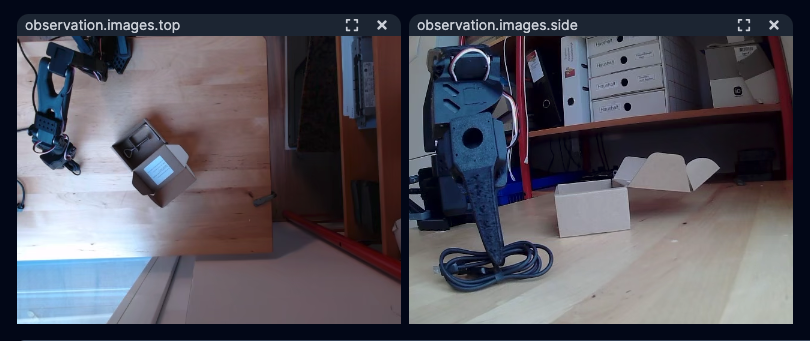

Data collection with LeRobot is amazingly straightforward. After getting comfortable with teleoperation, I wanted to dive into imitation learning, which meant collecting a dataset. To include visual observations, I created an improvised setup with an overhead webcam and a side camera.

I experimented with the settings and learned how to efficiently move to the next episode using the right arrow key. Pretty soon, I was ready to collect my first dataset. My goal: 50 episodes of picking a black USB cable from the table and placing it into a small cardboard box. The first dataset took about 25 minutes: roughly 2 episodes per minute. Each pick & place task only takes 10-15 seconds, but there was additional waiting time after resetting the environment where the script processes the collected data. I’m not sure exactly what happens during this processing, but it adds another 10-15 seconds per episode. Anyway, I’m a patient person, so I waited. The dataset automatically uploads to Hugging Face (you can find a visualization here), and I was ready to train my first policy.

Training ACT

I started with Action Chunking with Transformers (ACT), an imitation learning algorithm by Tony Z. Zhao from Chelsea Finn’s labs at Stanford. ACT trains a variational autoencoder and predicts sequences of action latents z instead of individual actions a. The sequence of action latents is then decoded into actual actions. The paper includes a nice architecture overview in Figure 4:

This design has two key advantages: the model is relatively lightweight and the predicted actions are smooth. Of course, this algorithm has been improved upon, for example, by the Diffusion Policy paper by Chi, Xu et al., which can model multimodal distributions. But for my case, a unimodal distribution was sufficient and worked very well.

Results

My first results were quite encouraging. After training for 100K steps on my NVIDIA RTX 3090 (about 3.5 hours, see wandb logs), I ran the ACT policy on my real robot. It picked up the cable on the first try! To be fair, I placed it well within the training distribution. Both the cable and cardboard box were in locations and orientations seen in the dataset. I started moving the cable and box around, and the robot largely succeeded as long as I stayed within the training distribution.

Once I moved away from the “known locations,” it got stuck. That’s not surprising. Why would the robot generalize to unseen locations when trained on only 50 episodes?

Adding a Wrist Camera

At this point, my setup had a top and a side camera, both fixed in place. I was curious whether the robot could perform similarly well if one of the cameras was attached to the wrist. Fortunately, my neighbor Roland has a 3D printer and was kind enough to print a wrist mount for me. I replaced the side camera with the wrist camera and repeated the exercise: collect 50 episodes and retrain an ACT policy.

This time, the robot failed most of the time. It could even barely pick up the cable if placed in exactly the same location as during training. Turns out that wrist-mounted cameras make it harder for the policy to succeed than a static side camera, quite an interesting observation in my opinion.

For subsequent experiments, I used three cameras: top, side, and wrist. This configuration resulted in very good performance for the unconditional ACT model:

Chapter 3: Finetuning VLA Models

After my initial success picking and placing a single cable, I was curious whether a pretrained VLA model would generalize to unknown locations. I finetuned smolVLA and X-VLA on my pick & place dataset, but the results were disappointing. The robot showed hesitant behavior during the initial movement and failed to position itself correctly during pickup.

I’m not sure what the problem was. Maybe the dataset was too small, the default finetuning hyperparameters were suboptimal, or the setup differences between pretraining and my custom dataset were too large (my camera placements were different). I would have been curious about finetuning \(\pi_{0.5}\), but I didn’t get to it. There’s always something to explore in the next project!

Chapter 4: Conclusion

This project was a great introduction to hands-on robot learning. The barrier to entry is remarkably low thanks to tools like Hugging Face LeRobot. I went from zero to a working pick & place policy in just a few hours.

The key lessons? Camera placement matters more than I expected, ACT is surprisingly robust for simple tasks, and while pretrained VLAs are promising, they probably need more than just a small dataset to work well on custom setups like mine.

There’s so much more to explore: larger VLA models and text-conditional tasks, multi-arm systems, Human-in-the-loop RL, and adding a mobile base like Aloha Mini or XLeRobot. If you’ve been curious about robot learning, I’d encourage you to give it a try. It’s very easy to get started and a lot of fun!

If you have any thoughts, feedback, or creative ideas, let me know what you think!

Links

- Datasets: Two-camera setup, Three-camera setup

- Models: ACT with three-camera setup, ACT with two-camera setup, Finetuned smolVLA, Finetuned X-VLA

- Weights & Biases Logs: ACT with three-camera setup, ACT with two-camera setup, Finetuned smolVLA, Finetuned X-VLA

- HuggingFace Imitation Learning Tutorial

Acknowledgements

- Gavin Cangan for lending me the robot and cameras.

- Roland for 3D printing the camera mount.

- Ilia (@ilialarchenko) for the amazing explainer videos on Youtube.

- Hugging Face for their opensource efforts.

- My dad and Barbara for providing office and amazing food.